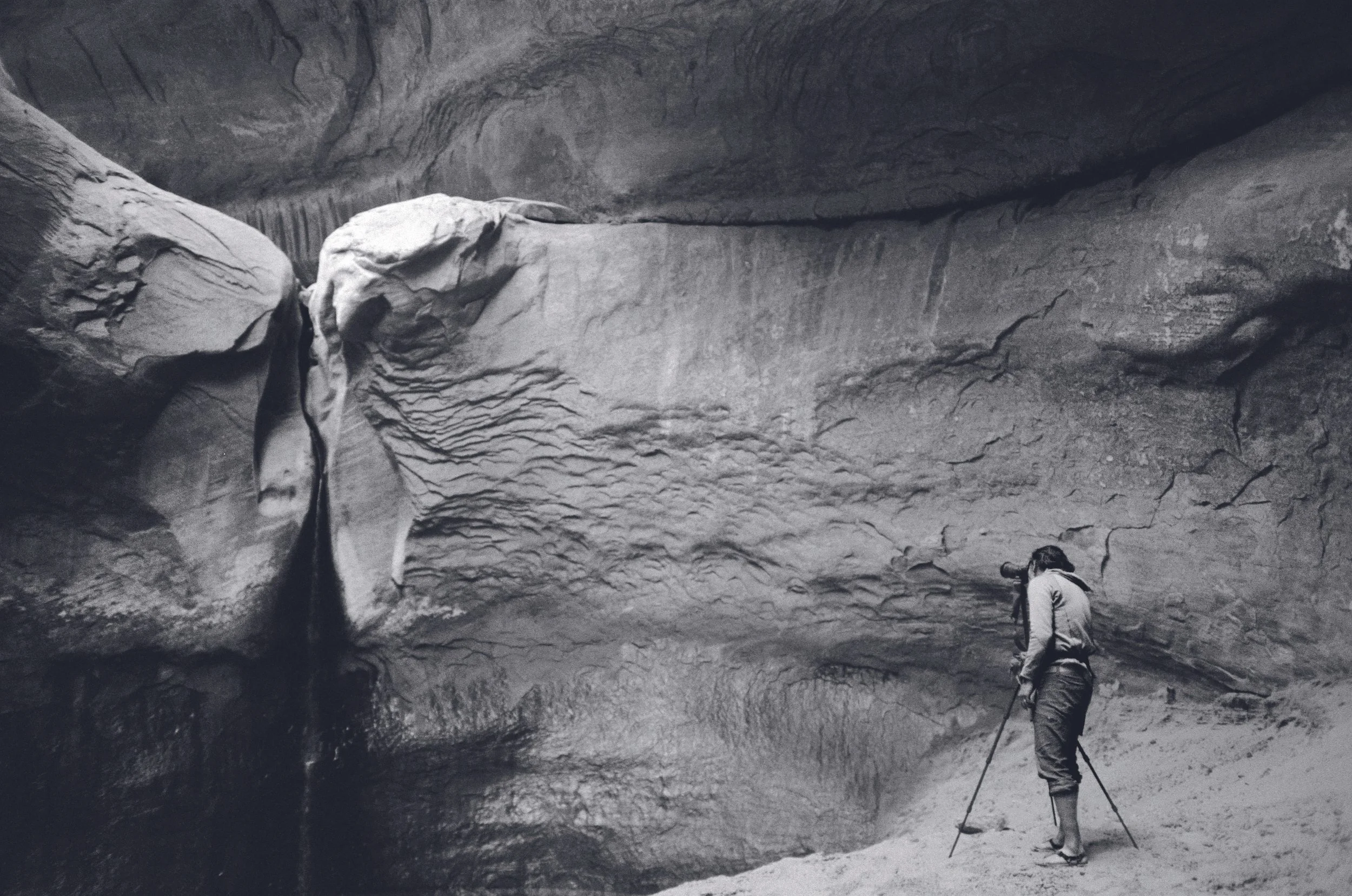

geography of hope: elliot ross

For the last half century, the heart of the Colorado Plateau has been drowned by man’s creation of Reservoir Powell. The American West is in its driest period in 1200 years, and as a result, reservoir levels are in sharp decline. With this loss, comes a silver lining. Glen Canyon is an unassuming name for a vast, interconnected network of 125 canyons that, from the air, resembles the human capillary system. Its artery is the Colorado River, connecting the delicate fingers that infinitely divide and converge. Its reappearance serves as a stark reminder of climate change, but also as a testament to nature's resilience. Before the completion of Glen Canyon Dam, little was known about what’s been called "America's Lost National Park" and “The Place No One Knew.” Today, it stands as the world's largest ecological restoration site, undergoing a remarkable transformation as resurgent native flora and fauna return. In the Fall of 2021, I began what has grown into a consuming effort to photographically survey Glen Canyon by foot, 4x4, airplane and boat as it undergoes a dramatic transformation. Through the dynamic aesthetics of this landscape, I’d like to invite you to contemplate your own relationship with water and consider supporting the conservation of this unprotected landscape. Herein lies a Geography of Hope.Please visit www.glencanyon.org to further your journey into the place we are getting to know.Your work deals a lot with social and environmental issues, what drives you to approach these topics?The way I see it, my role as a documentarian primarily is to elevate issues into the public consciousness. As we know, photography has the unique ability to succinctly convey complex meaning quickly and, when done right, impactfully. Social and environmental topics are often mired in polarization and emotion, and I believe that the simple act of seeing can bridge ideological gaps to a place of understanding. How does shooting film play a role in your work?Film plays an important role throughout my practice. Because of its finite nature, it requires me to make more considered choices in the moment: subject position, compositional arrangement, lighting angle and so forth. On a technical level, the use of film also broadens the ability to shape a unique feeling through the use of old glass and qualities certain filmstocks imbue. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, when photographing people it changes the dynamic. Analogue cameras, especially large and medium format ones, can create a sense of sacredness of the moment that people take seriously. In a way, it feels less like an extraction and more like a collaborative creation. Tell us a bit about your history and how you got into photography.Photography came into my life at a young age. I immigrated to the States when I was four, and was incredibly shy. My grandmother noticed my attraction to her camera and gave me a 35mm disposable. The camera created a safe space for me as I could hide behind the viewfinder, but still be present. Convergently, I spent a lot of time with my great-grandmother Edith Ross, who years earlier had been photographed by the great Robert Adams. I remember spending hours with one of his monographs, looking through black and white photographs of my new home in Eastern Colorado. Looking back, I think these two experiences defined much of my identity as it centered photography in how I saw most everything. What role do you think photography plays in your passion for adventure?Photography gives me a reason to dive into landscapes, stories and lives of others. Without that, I’m a spectator, an enthusiast. When I’m exhausted, the idea of a photograph compels me to push on or wake up for that bitterly cold sunrise. To name just a few, you’ve been published in National Geographic, TIME, The New York Times, & The New Yorker - What type of photo assignments/projects are you most excited to work on?I’m most excited to work on assignments that allow me to go deep and spend the critical time to build relationships, gain perspective and slowly distill big ideas into two-dimensional poetry. All of the publications you’ve listed have allowed me to do just that. Longform journalism is sadly an endangered species and this decline in dedication, in my view, correlates with the public's distrust in media. Having time is the secret sauce and the antidote to the “parachute journalism” that plagues our industry.Elliot Ross (b.1990) is a Taiwanese-American photographer based in Colorado. Ross’s practice is centered on human relationships with the land and defined by an uncanny intimacy with his subjects. Through his sprawling projects, Ross investigates how landscapes – both natural and artificial – shape community and culture. His ongoing works examine: relationships to water in the American West, the dynamism of the Anthropocene, how indigenous communities on the frontlines of climate change are confronting a loss of home through self-determination, and how national borders both shape and divide identity.

originally published in print in the adventure issue #8, March 2024