Arielle Weenonia Gray

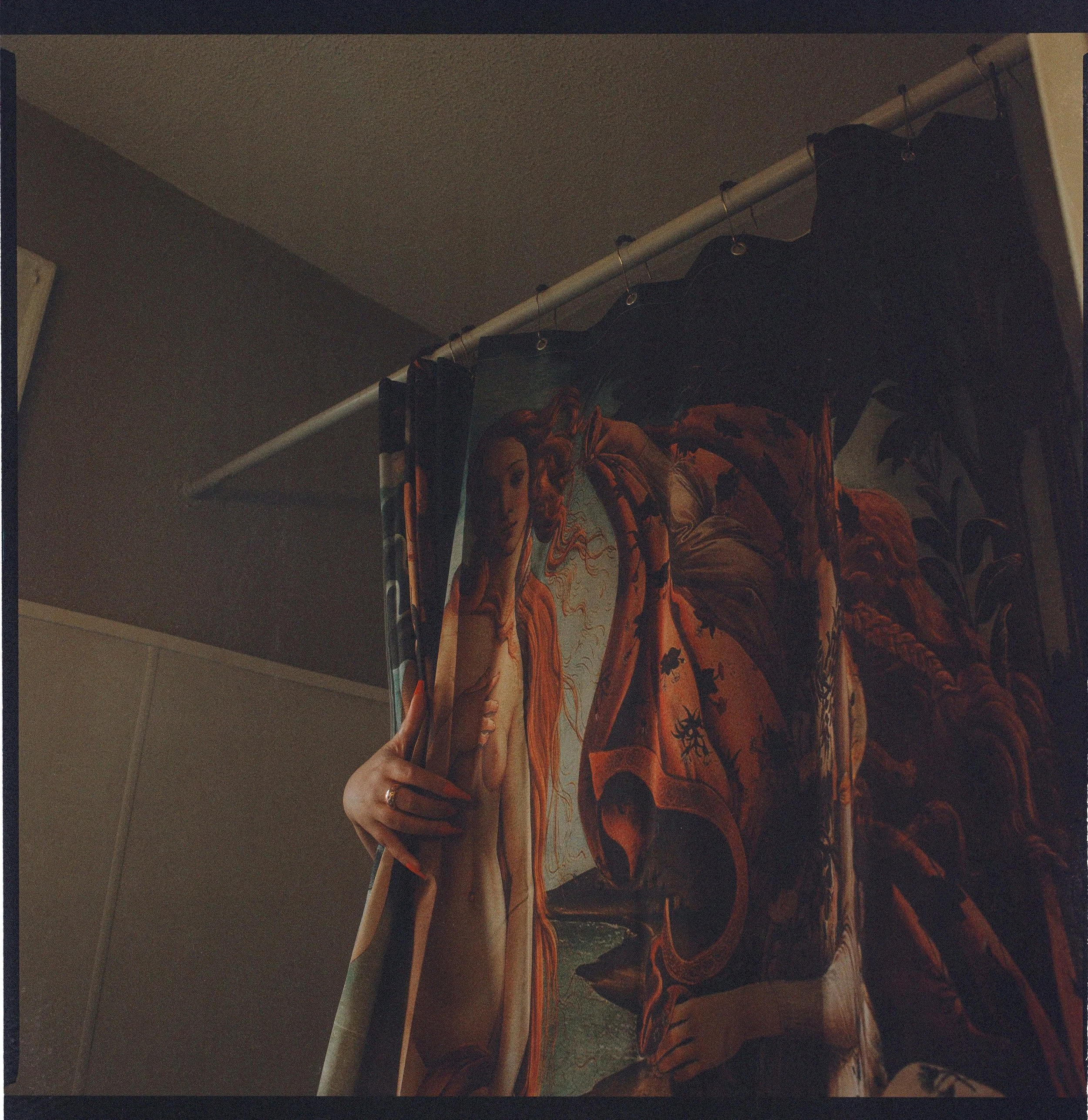

Considering my grandmother’s recent passing, I cannot help but think about self-portraiture as a way we, as photographers, hold mirrors to our subjects, yet, in turn, they hold a mirror to us as well. As a granddaughter, daughter, and sister, my Nana, mama, and sister, and I walk through a never-ending hall of mirrors with one another. We are hand in hand. We are looking at, gazing upon, loving on, and longing for a world of warmth down an icy hall of looking glass. I was given this assignment to write about self-portraiture and my participation in creating images of myself. I don’t feel I can do that without speaking to where it originated and sharing some about the women who gave me the lifelong privilege of looking and making. I think about Arthur Jafa and Deana Lawson’s film Centropy. I watch it here and there throughout the year as a ritual. If you look it up on the Guggenheim’s website, scroll down about midway down the page, click “play”, and after the title, the black box slowly pops up into a magenta constellation of white-hot heat and the deep black darkness of space. Jafa begins the video telling Lawson “We existed before existence” and we are housed and born within those that come before us. In my photographs, I feel this when I hold photographs of my grandmother with a Land camera, making polaroids of lovers, friends, and family at John F. Kennedy’s Memorial Plaza in Dallas. This was an age where they could still move freely about the cabin. I was mystified and touched by the presence and absence of something I could no longer touch with my own hands. I tend to feel this when I look at images of my mother at twenty-nine, newly married to the love of her life. I don’t have that; I feel touched and untouched by it all at once. I have photographs of my own where I get my braces taken off, hold hands with my father, or blow out candles on a Barbie cake. I wonder what they feel about all of this. My mother held us in her vision so closely during childhood. Before we had digital cameras, we had the One-Hour Photo at Rite-Aid. I reference my mother’s photoshoots as my first conscious interactions with the camera. On her days off from Lowe’s, she would dress Iyana and me in matching black leather jackets, striped shirts, and sunglasses. To her, we were twin canvases. Black and white film and prayer hand poses were our go-to's. We would get our hair blown out, don sundresses, and walk up the hill our house sat on as if on location for a fashion magazine. After everything was shot, we’d pack ourselves in her beige 1996 C300 Mercedes, drive to Rite-Aid to drop off photos, and walk around the corner to the Movie Gallery, begging for cotton candy and hoping to rent the latest Pokémon movie. Seeing my blown-out afro, my gappy grin, and the excitement in my eyes in those glossy four-by-sixes was the magic. I would tell myself “Yes, this is me” and it was. I felt like an actor on a stage my mother had built all for us. It was significant. It was nourishment for two girls without the company of other children on a hill in Moundville, Alabama. At four or five, I obviously could not verbalize the “why” of it all. Why would I question it? I was a kid and it was euphoria to me. I would not be able to even attempt to put words to it until twenty years later when I planted myself in that Pool in New Haven. My great aunt, Bessie, was my grandmother’s last living sister. She passed in November 2021 right before bell hooks. Not only was this a loss for our entire family, but it was a major loss for my grandmother. There had been fifteen of them all born in Myrtlewood, Alabama to my great grandparents, Weenonia and Council. The chord this struck in me was dissonant. There was a doubling down of a realization we come to frequently: there will be a day when there is just one left. To myself and my twin sister, this spells the confirmation and invitation to insanity for us. I cannot imagine life without her. My second critique during my first year of graduate school was in 2021. I remember being asked if a portrait of my sister, Iyana, stood in for a portrait of me. This was a question that hung in the air, above the fluorescent lights and it reverberated from the querent to the entirety of the audience in the Pool. I would be the last in the room to receive its vibrations after an art school awkward silence. My classmates ogled and awaited an answer that was either prolific or pitiful. To tell the truth, it was a portrait I made because like all graduate students (all art students, really) thought about Death and its partner, Grief, through their work at some point or another. I wanted to photograph my sister because of Bessie’s passing and to attempt to come to terms with the inevitable. I wanted to be able to stop time in these moments just so I could look and hold on to what I care about the most through my lens. I’d made the photograph in our front yard in Alabama. My sister’s hair had recently been bleached and toned to a honey blond, creating a series of brown gradients throughout her curls. I pulled a red corset, furry black coat, and my reflector. Wearing the red corset and the black coat, Iyana listened as I instructed her to squat down in our driveway in front of purple morning glories, and close her eyes as I attempted to find the supplementary light I needed from the silver side of the reflector. I just wanted to see her. I wanted to hold her angelic face in silver light with morning glories opening behind her. That seemed like that was it. Of course, I didn’t say all of this to the panel. I didn’t have pretty or complex words. I didn’t have an idea or reference based in some sort of critical theory to supplement conversation with. I chose to be honest. I chose to emphasize the intention behind the photograph but to also communicate how unsure I was of how to respond. I told them I didn’t know but would think about it, and work through it by photographing myself more often. I had never thought of it in that way, but it made sense. It was an unconscious decision being verbalized for the very first time. At the time, I could not begin to find an answer to the question being posed. I was grateful I had enough confidence, to be honest, and reply I did not know the answer to the question but would think about it. It was not a trick question, thankfully. It was and is a question for me to ponder past, present, and future. These are the best questions to receive during a critique. I began to think of people I photographed as mirrors. What did that say about me? How much of myself am I putting into this and how much is my subject able to contribute? Does any of this matter so long as a portrait is captivating? In my head it seemed logical that to understand my process, my modus operandi, I would need to turn the lens onto myself—see and work with myself the way I work with other people. I turned to my heroes: Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, Nadia Lee Cohen, Tommy Kha, and Claude Cahun, I find and found them to be exemplary in their varied approaches to the self-portraiture genre. In addition to grief, the question took me on the route toward the root of my discomfort of having pictures taken of myself by others (except my mother, of course). I never liked the class pictures we took in school. My mom would straighten our hair the night before and we could only pray and “sleep pretty” as she called it. I’d try to prop my head up on my elbow so my hair wouldn’t get ruined by my tossing and turning. This almost always failed and resulted in a frustrated mother’s attempt to straighten hair, make breakfast, fix lunches, assemble our pre-selected picture day outfits, and her work attire in under fifteen minutes. My eight-year-old nerves and the playground would go on to undermine all of Mom’s hard work regardless. My stomach would turn in knots as I waited in the assembly line to have my picture taken. I would always hope and pray the proof that would eventually arrive would be somewhat acceptable. I imagined my eyes and my mouth smiling together and creating something acceptable for my mother and grandmother. My hair would be just as my mother had done it that morning (in later years, she would begin to show up to the school with the flat iron in tow just to touch us up before the photos). My feelings about other people photographing me was also something I considered, to myself during that critique as the question was asked. Other people photographing me had begun to make even more intricate knots in my stomach in the years to follow my early years. It started during high school. I grew up in the beginning of Facebook, Snapchat, and Instagram. No one was safe in those days. We were desperate to capture every single mundane moment with wonder and obsession. I still don’t know why. My body and mind had to grow up in a world where everything was becoming more and more dependent on how we appeared in images. It was crazed even. On one hand, the possibilities were endless. We could image ourselves any way we wanted. “Selfies” were a big part of the conversation, I remember. On the other hand, the possibilities were endless. Coming of age as a Black girl in the Deep South during the early 2010s, my being seen was a blessing and a curse. I was and am what in the South call a “Stallion”. “Tall and fine” if you look it up in the Urban Dictionary. I am five foot ten with legs like tree trunks, and hips that touch more surfaces than Lysol, and this has come across as relatively attractive to most people. I grew up being told to smile and vehemently being told to pull my shorts down as my body developed. I couldn’t help it. My thighs rub together when I walk. I was one of the first in my fifth-grade class to have a period, and it felt like a huge spotlight was placed on me from then on. What happened to my body seemed to be everybody’s business but mine. White schoolteachers offered little solace and praised my smaller white counterparts for outfits I could never possibly wear in the same way they did. They could get away with wearing it. I would not get past the front door with it on. I felt isolated and unsure of where I could fit. I would later learn to forego fitting in and take up space. The only solution I could think of was imagining myself by myself and for myself. This and therapy... quite a good bit of therapy. I had never sought out help in this way. I didn’t know what to expect. My sister had recently started her healing journey during our undergrad years. I would learn from her that it was possible to have my own preferences for whom I would receive care from. The first few sessions always felt inconclusive. I would talk for the majority of the session and felt I would receive maybe five minutes of feedback. I had been there for months before I felt the change in my mindset and noticed patterns in my behavior that had previously set me up for failure and insecurity. Therapy would become a tool in navigating the hall of mirrors. I’d chosen to begin seeing a psychiatrist and a non-clinical mental health counselor in the fall of my first year of graduate school after I’d almost had a nervous breakdown over a class photo I had taken with my cohort. We’d toured the studios and facilities during orientation, and after the tour, we had decided to commemorate the moment with a group photo. I couldn’t tell if it was a post-pandemic habit or if this was just one of my “icks.” A group photo after looking at our future studios had given me the same cringey feeling I get when people applaud when the plane lands. More than that, my classmates giggled at the photo upon reviewing it. My insecurities and paranoia led me to believe they were laughing at me. Of course, they weren’t—but how could they not be? I was standing so far from everyone else with a half-attempt at a grin that looked more like a grimace on my face. My back was hunched, my wig pushed so far back the braids underneath had made their cameo in the picture, and my lazy eye!! God, my lazy eye had made a reappearance the moment I had let the renewed discomfort take over. For better or worse, I have often seen myself through the words of others. Their impressions have shaped the reflection I hold of my face, the shape of my eyes, my shoulders, my chest, my posture, my chin, and any other part of me that others desired to hold. It isn’t a healthy model by any means. We all do it at some point or another, I know. Conversely, self-portraiture has always felt like a kind of marriage—a uniting between myself and the lens at the end of an aisle. I am bound by an intimate exchange of glances from one of my selves to another. I look at myself and hold myself from the moment I frame my composition, to the moment I breathe in. I take that breath in, I say ‘I do’ to make something between myself and the camera. I think about everybody who has walked this path before me. I remember being extremely pressed to find subjects I felt I could photograph during graduate school. I also thought about love and longing for a while. I say all of this to communicate something about self-portraiture that transcends the end product. This is how it feels for me. However, I cannot say it has always been easy to achieve. It’s a one-woman show for me at the end of the day. In February of 2022, I so badly wanted to create a heart-shaped hot tub photo at one of those kitschy honeymoon hotels. I’d consulted Gregory, my department head, and he told me (and I’m paraphrasing), “yes, it’s been done but not by you yet.” That was all I needed. I booked the hotel, noting that I wanted a room featuring a red heart-shaped tub, and began to conceptualize from there. I imagined the room with red carpets, mirrored walls and ceilings, a round red bed, and the red heart-shaped tub. In my mind, I was poised in an aqua sea of bubbles with a cable release in one hand and a direct engagement with the camera in my eyes. But here’s what actually happened: On the day I was supposed to head out to South Amboy from New Haven, I awoke to a text from my would’ve-been assistant/moral support. They’d overdrank the night before, and I would have to find a replacement. I’ve never been too good at finding replacements because I was definitely not the most socially connected person in art school, and I trusted so few people at that time. The journey to Jersey hadn’t even started yet, and I was frustrated already.I couldn’t not go. If I didn’t go, the one-hundred-and-nineteen-dollar deposit would have weighed on my little broke artist heart so heavily. I loaded my suitcase with my strobe, hot lights, various props, and got into the car. My stomach twisted in knots as I made the trip. I felt claustrophobic while stopped in traffic in the Bronx. There was also a forecast for snow, and the Alabama girl in me didn’t know if my heart could take that and the Bronx today. Knots with the utmost tension formed in my back. To relieve some of it, I stopped for chicken nuggets, adjusted my glasses, and popped ibuprofen before merging back onto the road. My grandmother would be calling every hour on the hour as I made this trip. It was a break from my listening to The Year of Magical Thinking on Audible. She worried so much about me from home in Alabama. Phone calls were never enough. She was always proud of my choices, but it didn’t matter to Yale if they gained a student - she lost a granddaughter, even if only for a two-year period. I arrived at the motel in a coat that I felt would assure coverage of all my bodily assets from certain eyes. My mom has always watched a lot of the ID channel, and it prompts a reiteration that human trafficking is everywhere. Especially for a lone woman on the road with a big yellow suitcase. When I turned the handle and stepped in, I immediately noticed an icy blue hue I hadn’t expected. Worst of all, there was no heart-shaped love tub, but a white, square tub embedded with iridescent glitter. I was pissed. But how could I make use of the time and effort I had already put into this trip? I’m not the type to argue with management and, based on my Spidey Senses upon arrival, didn’t feel too comfortable in that location to make my presence noticeable beyond check-in. I quickly made use of some of the space by setting up my tripod and posing on the bed under the ceiling mirrors, moving the white leather couch, posing there, and quickly packed my shit up and left. I cried in the car and prayed before getting back on the turnpike. I would later return to New Haven with a sore back and attempt to take myself out for a pity party at my favorite bar, where I would drink my favorite lavender cocktail and eat a cheeseburger. At just the most imperfectly perfect moment, I caught sight of a boy I’d been seeing on a date with another person. It didn’t bother me much that he was with someone else. We weren’t together, but it still made me feel something mournful and empty inside. The Uber home had been so necessary due to the multiple freebies my favorite bartender gave me at said favorite bar. Martinis and negronis would follow me up the stairs as I got into my apartment and pulled out my strawberry flavored cones and rental camera. At the time, I was wearing this long, rosy ginger wig and enjoyed wearing this hair color with pink clothing (especially soft pink sweaters). I would need to balance my camera in a precarious position to get an image a critic would later say “almost didn’t feel like a self-portrait." This was a huge compliment to me. In all honesty, I was seeing myself as another version of myself, directing her in a way that felt as though I were photographing someone else...but not. I showed that image in the 2022 critique, along with the motel image, a few others where I wore rollers in my hair and brown stockings with a matching bra, and a few others I cannot remember. It felt so unintentional, but regardless, there it was. It was my hall of mirrors for that moment in time. The intention was there whether I had been aware or not. Looking back, I realize that self-portraiture has always been more than just capturing an image—it’s about constructing a reflection of the self, whether intentional or subconscious. It can also be about constructing a world of one’s own, surpassing the confinements of a room of one’s own. This is something I see so clearly in the work of artists who have made self-portraiture a central part of their practice. I am always moved by the artists who have embraced this form, with Carrie Mae Weems being the first person that comes to mind. I write this with the assumption that we are all aware of The Kitchen Table series. We have seen the beautiful monochromatic, tonally vast square images of the artist posed and poised at her kitchen table as she creates a world of her own for herself. The ability to build a world of your own is precious and difficult. You must use all five of your senses. To be able to see, taste, smell, touch, and hear a world within yourself is a powerful inner gift that’s tested once you imagine it. I think about the smoky atmosphere from cigarettes and the haze a passionate card game creates between the man and woman in Untitled (man smoking). I want to hear jazz in the background, maybe not even jazz. Maybe just the sounds of brown liquor rushing into their tumblers and the satisfying shuffle of the thick paper cards in their knowing hands.I’d heard about The Kitchen Table series in my first photography (darkroom) class as an apparel design art major at the University of Alabama around 2017. It wouldn’t be until 2024 that I would learn of an even closer branch on my photography family tree. I’d never known my grandmother to be one to pull out a camera. Since birth, it had been up to my mother to always carry her camera with her to document our lives together. However, I unearthed a dark green canvas volume of polaroids from a nine-foot wardrobe in my grandmother’s house one dark, Alabama summer day.The spine was severely damaged and outside on the cover “Ramsey” had been geometrically scrawled onto the cover in black ballpoint pen. One of my grandmother’s former last names. She knew how to keep a man. I opened the album and witnessed the neat little squares of life on its pages. In awe, I could see vignettes: my Nana posing with her camera, smiling; an image of a random white man on a plane to Dallas; and Nana leisurely lying on a round bed—like the image I wished I’d made in South Amboy. The light in her eyes these images possessed was the same illuminating light I saw in them at the end of the summer in 2024. I felt even more connected to her.

I saw myself in her. I hope she sees herself in me. My grandmother had unwittingly made her own series. It was filled with an ardent love and awareness of love in the rooms she stepped into. It has been aspirational as much as it has been inspirational to me. There are many more questions I have for other photographers who participate in imaging themselves. I wonder if any of my heroes and peers ever feel similarly. Or that maybe the appeal and goal is to build these questions, answers, and ideas for themselves. I would wonder what Carrie Mae Weems would say to this. I would wonder what Arthur Jafa would say to this. I would wonder what David Lynch would have to say about this. I would wonder what my grandmother would have to say about this. essay & images by arielle weenonia gray

Editor’s note: an excerpt from this essay & the portfolio of images appear in print in the balance issue #11, Spring 2025